The Miracle of Formation and Growth

The journey from a single, undifferentiated fertilized egg—a zygote—to a complex, fully functional organism is perhaps the most astonishing biological process in all of nature. This incredible transformation is the core focus of Developmental Biology, a field dedicated to unraveling the precise mechanisms that control growth, differentiation, and the formation of tissues and organs. It seeks to understand how the one-dimensional information stored in the DNA blueprint is translated into a three-dimensional, sentient being with billions of specialized cells.

This intricate process involves a coordinated, orchestrated cascade of cell divisions, cell movements, and gene expression changes that unfold with breathtaking accuracy in both space and time. Errors in this delicate choreography can lead to birth defects, disease, and developmental disorders, highlighting the system’s fragility. Understanding the signaling pathways and genetic switches that govern this journey is not just a matter of academic curiosity. It is the fundamental key to unlocking regenerative medicine, understanding the roots of cancer, and perhaps even reversing the debilitating effects of aging.

The Earliest Steps: Fertilization and Cleavage

The profound process of Developmental Biology begins with the critical, foundational event of Fertilization. This involves the crucial fusion of two specialized sex cells, the sperm and the egg, to successfully create a new single-celled organism.

This is immediately followed by a period of extremely rapid cell division known as Cleavage. This initial stage of rapid growth lays the essential groundwork for all subsequent complexity in the organism’s structure.

A. Fertilization: The Beginning

Fertilization is much more than just the simple merging of genetic material from two parents. It is a highly regulated, complex process that powerfully activates the egg. It also simultaneously establishes the basic spatial polarity of the future organism.

-

The sperm must successfully penetrate the outer, protective layers of the egg. This penetration triggers a crucial, immediate protective mechanism known as the Cortical Reaction. This mechanism actively prevents fertilization by multiple sperm (polyspermy), which would be fatal.

-

The fusion of the two Haploid Nuclei (containing half the necessary chromosomes) successfully forms the single Diploid Zygote nucleus. This act effectively restores the full, correct chromosomal complement for the new individual.

-

The specific point of sperm entry often helps to precisely define the future Anterior-Posterior (head-to-tail) axis. It may also define the Dorsal-Ventral (back-to-belly) axis of the rapidly developing embryo.

B. Cleavage: Rapid Cell Division

Following successful fertilization, the zygote immediately enters a rapid and dramatic phase of mitotic cell division called cleavage. This process dramatically increases the number of cells. Crucially, it does so without increasing the overall bulk size of the entire embryo.

-

The resulting cells, individually called Blastomeres, get progressively smaller with each successive division. They are still entirely contained within the original, protective volume of the egg.

-

Cleavage eventually leads to the formation of a solid ball of cells. This structure is known as the Morula, representing the first visible step in multi-cellular organization.

-

The specific pattern of cleavage (e.g., radial, spiral, rotational) is highly conserved and strictly species-specific. It is dictated entirely by the initial amount and precise distribution of energy-rich Yolk within the egg cell.

C. Formation of the Blastula

As the intensive process of cleavage progresses, the solid morula transitions into a distinctive hollow ball of cells called the Blastula. This specialized structure contains the first clear, visible signs of cell differentiation.

-

The blastula consists of a defined outer layer of cells. It also encloses an internal, fluid-filled cavity known as the Blastocoel.

-

In mammals, this blastula is more specifically called the Blastocyst. It contains two distinct cell populations: the crucial Inner Cell Mass (ICM) and the outer Trophoblast.

-

The Trophoblast will eventually contribute exclusively to the placenta and supporting membranes. Meanwhile, the ICM gives definitive rise to the entire embryo itself, marking the first major cell fate decision.

Laying the Blueprint: Gastrulation

Gastrulation is arguably the most critical and structurally complex stage of early embryonic development. During this profound process, the simple, single-layered blastula is dramatically transformed into a multi-layered structure called the Gastrula.

This stage involves massive, highly orchestrated cell movements and wholesale tissue rearrangements. It establishes the three fundamental germ layers from which all the body’s tissues will ultimately arise.

A. Cell Movement and Invagination

Gastrulation is driven by highly complex and coordinated movements of the individual blastomeres. These essential movements include rolling, precise folding, and large-scale migration of cell sheets.

-

A key, defining movement is Invagination. This is where a sheet of cells folds sharply inward, much like pushing in one side of a soft, deflated balloon. This action forms a new internal cavity.

-

This crucial inward folding establishes the primitive gut tube. This ancient structure is known as the Archenteron. The external opening to this new gut cavity is the Blastopore.

-

The final fate of the blastopore (whether it becomes the mouth or the anus) is the primary distinction between two major animal groups: Protostomes and Deuterostomes (which includes all vertebrates).

B. The Three Germ Layers

Gastrulation results in the successful formation of three distinct, concentric tissue layers within the embryo. Each of these vital layers is rigorously committed to forming specific organs and tissues in the adult body.

-

The outermost layer is the Ectoderm (literally the “outer skin”). It is fated to become the epidermis (outer skin), the entire nervous system (brain and spinal cord), and all sensory organs.

-

The innermost layer is the Endoderm (the “inner skin”). It will form the critical lining of the digestive and respiratory tracts, as well as associated internal organs like the liver and pancreas.

-

The middle layer is the Mesoderm (the “middle skin”). It is the most diverse, forming all muscles, bone, cartilage, the circulatory system (heart and vessels), kidneys, and internal reproductive organs.

C. Cell Signaling and Induction

The precise fate and movement of cells during the chaotic process of gastrulation are meticulously controlled. This control is achieved by continuous chemical communication between neighboring cells. This vital, continuous communication is called Cell Signaling or Induction.

-

Cells constantly secrete specialized signaling molecules that act as localized chemical cues. These molecules instruct nearby cells to commit to a specific germ layer or follow a predefined migratory path.

-

For a clear example, signals emanating from the developing Mesoderm are absolutely crucial for inducing the overlying Ectoderm to develop correctly into the Neural Plate. The Neural Plate is the definitive precursor to the entire nervous system.

-

The Spemann-Mangold Organizer (first discovered in amphibian embryos) is a small, powerful region of the embryo that sends out these essential organizational signals. It effectively organizes the definitive fate of all surrounding cells.

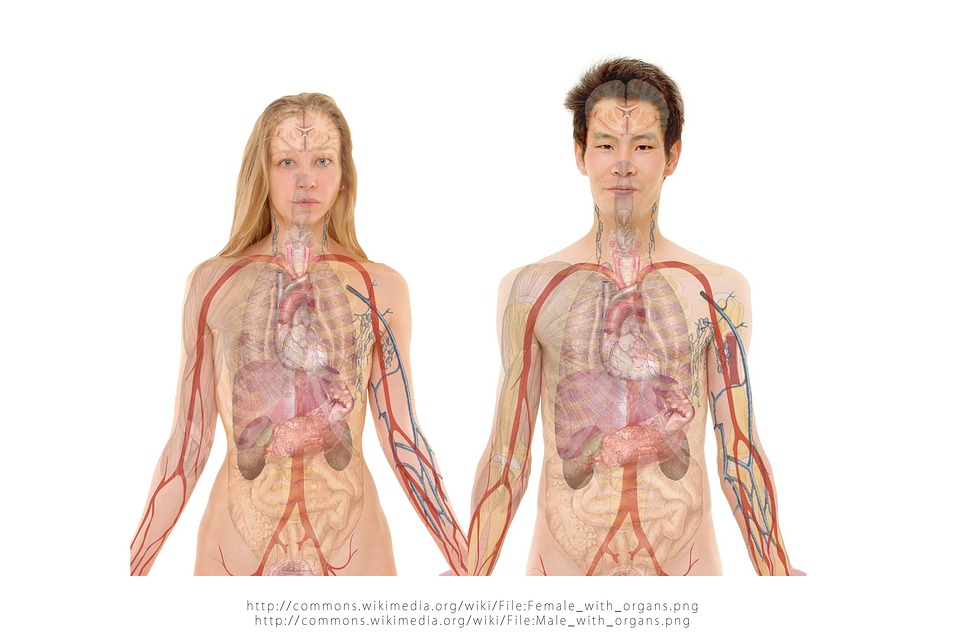

Shaping the Body: Organogenesis

Once the three fundamental germ layers are reliably established, the embryo enters the detailed and complex phase of Organogenesis. During this stage, the layers actively fold, bulge, and differentiate into recognizable, functional organs and defined body structures.

This vast process involves countless specific cell-cell interactions. It requires the precise, timed activation of large, interconnected networks of specialized developmental genes.

A. Neurulation: Forming the Nervous System

Neurulation is the specific process where the ectoderm differentiates and folds in on itself. This action forms the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord). It is consistently one of the earliest, most critical events in vertebrate organogenesis.

-

The Neural Plate (initially a flattened sheet of ectoderm) dramatically rolls up and fuses along its edges to form the Neural Tube. This tube will eventually become the definitive brain and the spinal cord.

-

A failure of this tube to close properly along its length results in severe birth defects. These are collectively known as Neural Tube Defects, such as spina bifida.

-

Specialized cells that pinch off from the top of the folding neural tube form the Neural Crest Cells. These are highly migratory and give rise to a remarkably diverse range of tissues, including parts of the peripheral nervous system, pigment cells, and facial cartilage.

B. Somite Formation

The mesoderm tissue, which lies immediately adjacent to the developing neural tube, segments into highly organized blocks of tissue called Somites. These critical structures dictate the fundamental segmented pattern of the entire vertebrate body plan.

-

Somites appear as repeated, uniform segments along the anterior-posterior axis of the developing embryo. They give rise to the segmental organization of the ribs, vertebrae, and all the axial muscles of the back.

-

Cells within the somite differentiate into three main, distinct parts: the Sclerotome (forming the vertebrae and ribs), the Myotome (forming muscle), and the Dermatome (forming the dermis/skin).

-

The final, determined fate of a specific somite cell is strictly determined by local signaling molecules. These molecules originate from the nearby neural tube and the adjacent notochord structure.

C. Apoptosis: Programmed Cell Death

Development is certainly not just about adding new cells; it also involves the precise, targeted, and deliberate removal of cells through a highly regulated process. This essential process is called Apoptosis or programmed cell death.

-

Apoptosis is absolutely essential for sculpting complex, final structures and for eliminating unnecessary cells that served a temporary function. For example, it cleanly carves out the spaces between the developing digits to form individual fingers and toes.

-

It is also critically important for actively removing abnormal or potentially harmful cells during development. This action rigorously maintains tissue homeostasis and structural integrity.

-

Defects in the delicate regulation of apoptosis can lead to problems like webbing between digits (syndactyly) or can tragically contribute to the uncontrolled cell growth characteristic of aggressive cancer.

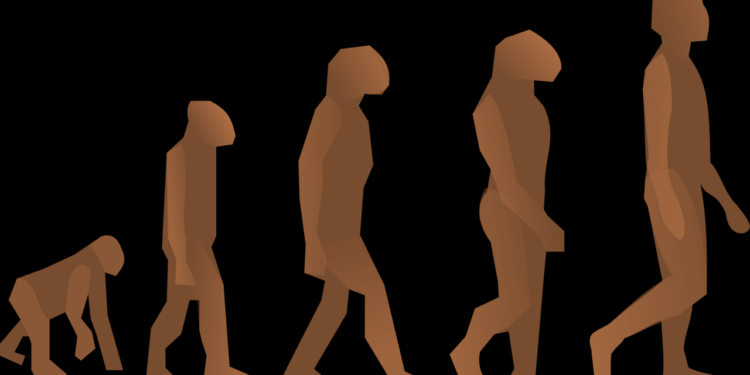

Genetic Control of Development

The entire complex process of developmental biology, from the very first cleavage division to the final organogenesis, is meticulously regulated. This regulation is controlled by a relatively small, highly conserved set of master control genes. These specific genes act as crucial master switches, controlling the ultimate fate and distinct identity of every cell.

The remarkable concept of using a modular set of genes to control spatial identity along the body axis is one of the most remarkable and unexpected discoveries in the field.

A. Homeotic Genes (Hox)

The Homeotic Genes, and specifically the Hox Genes in the animal kingdom, are the master control genes for body axis identity. They precisely specify the identity of body segments along the anterior-posterior axis of the animal.

-

Hox genes are uniquely arranged in the genome in the exact same physical order as the body parts they control. This phenomenon is known as Colinearity. They are crucial for ensuring that the head grows on the anterior end and the tail on the posterior end.

-

Mutations in these critical genes can cause bizarre developmental transformations. For example, an insect might disastrously grow a leg where an antenna should be, or a vertebrate might grow a misplaced rib.

-

The entire Hox gene complex is highly conserved across virtually the entire animal kingdom. This strongly demonstrates the shared evolutionary heritage and the ancient origin of these fundamental developmental mechanisms.

B. Positional Information and Morphogens

Individual cells ultimately determine their specific, differentiated fate based critically on their precise spatial location within the developing embryo. This concept is fundamentally called Positional Information.

-

Cells sense their exact position by actively responding to specific concentration gradients of diffusible signaling molecules. These chemical signals are called Morphogens.

-

A high concentration of a specific morphogen might instruct a nearby cell to become a highly specialized neuron. Meanwhile, a low concentration of the exact same signal might instruct a distant cell to become simple skin.

-

The most famous and well-studied example is the signaling molecule Sonic Hedgehog (Shh). This crucial molecule controls the precise specification of various structures, including the correct polarity of developing limbs.

C. Differential Gene Expression

All cells in a complex organism, from a highly specialized nerve cell to a simple liver cell, share the exact same genetic blueprint (the DNA). Their profound functional differences arise exclusively from Differential Gene Expression.

-

Only a small fraction of the total genome is actively expressed (transcribed) in any given cell type at a given time. This specific, unique pattern of active genes dictates the cell’s function and identity.

-

Transcription Factors are specialized proteins that bind to specific regions of the DNA. They act as molecular switches, turning specific target genes either “on” or “off” in response to external signals.

-

The intricate, time-regulated activation and repression of thousands of genes are the ultimate, physical molecular mechanism successfully driving the entire complex process of differentiation and development.

Stem Cells and Regeneration

The profound study of developmental biology fundamentally informs our entire modern understanding of Stem Cells. Stem cells are defined as undifferentiated cells that hold the potential to renew themselves indefinitely. They can also differentiate into specialized cell types upon receiving the right signal.

This crucial area of research is the cornerstone of the rapidly evolving field of Regenerative Medicine. This field aims to efficiently repair or replace damaged tissues and organs using biological methods.

A. Types of Potency

Stem cells are carefully categorized based on their functional Potency. This term refers to the range of cell types they are capable of becoming. This ability accurately reflects their current stage in the natural developmental process.

-

Totipotent cells (like the fertilized zygote) can form all cell types. This includes the entire organism and the surrounding extra-embryonic tissues (like the placenta).

-

Pluripotent cells (like those found in the Inner Cell Mass of the blastocyst) can form any cell type within the body. However, they cannot form the external placenta.

-

Multipotent cells (like adult hematopoietic stem cells found in bone marrow) can only differentiate into a limited range of cell types. This is typically restricted to one specific tissue lineage, like blood cells.

B. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

A major, conceptual breakthrough allowed scientists to essentially rewind the developmental clock of specialized adult cells back to an earlier state. This remarkable technique generates Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs).

-

Adult somatic cells (like easily accessible skin cells) are genetically reprogrammed. This is achieved by artificially activating a small set of specific Master Regulator Transcription Factors within them.

-

These manufactured iPSCs behave remarkably much like natural embryonic stem cells. They can differentiate into almost any cell type in the body. This offers an ethically less controversial source of pluripotent cells.

-

iPSCs are invaluable for personalized medicine. They allow researchers to create accurate disease models using a patient’s own unique genetic background for effective drug testing and in-depth disease study.

C. Regeneration and Repair

Understanding the specific developmental processes that build an entire organism is crucially important for activating the dormant capacity for Regeneration in adult human tissues.

-

Some impressive organisms, like the humble salamander, can regenerate entire limbs or organs perfectly. They achieve this by effectively reactivating ancient embryonic developmental pathways in their adult cells.

-

In humans, our natural regenerative capacity is very limited. It is primarily restricted to simple wound healing and minor tissue turnover. We lack the ability to reactivate full, complex organ formation.

-

Developmental biology research aims to precisely identify the specific molecular signals and genetic switches that govern successful regeneration. This knowledge could potentially be leveraged to enhance human repair mechanisms dramatically.

Conclusion

The transformation from a single cell to a complex organism is a breathtaking process at the heart of Developmental Biology, commencing with the precise fusion during Fertilization and rapid cell divisions known as Cleavage. The critical stage of Gastrulation establishes the three fundamental tissue layers—the Ectoderm, Mesoderm, and Endoderm—through highly coordinated cell movements and Induction signals. Following this, Organogenesisproceeds, involving specialized events like Neurulation for the nervous system and the crucial, sculpting role of Apoptosis.

The entire choreography is meticulously controlled by a universal, ancient genetic toolkit, featuring master regulator genes like the Hox Genes and concentration gradients of Morphogens. This profound biological understanding is the foundation for modern Stem Cell research, which carefully categorizes cells by their Potency and has led to the groundbreaking creation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs).

Ultimately, the field seeks to unlock the mechanisms governing natural Regeneration in simpler organisms. This knowledge holds the immense potential to revolutionize human medicine. It promises to repair and replace damaged tissues in the future.