The Revolution of Precise DNA Editing

Imagine possessing a universal biological word processor capable of navigating the billions of letters in an organism’s genetic code. This word processor can precisely locate any typo, flaw, or unwanted sequence. It can then correct it with unprecedented ease and accuracy. This concept, once firmly in the realm of science fiction, is now a powerful, accessible reality thanks to the development of CRISPR-Cas9.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a revolutionary technology that has fundamentally transformed modern biology. CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, an initially obscure defense system found in bacteria and archaea. Scientists have brilliantly re-engineered this system to function as a molecular pair of scissors.

This allows them to make precise, targeted changes to the DNA of virtually any organism, including humans. This capability bypasses the slow, inefficient methods of genetic modification used for decades. It has instantly accelerated research into incurable diseases, agriculture, and fundamental biological processes. The power of this genetic scalpel is immense, opening the door to curing genetic disorders and redesigning entire ecosystems. However, this transformative power comes with profound ethical, social, and safety questions. These questions demand careful, immediate consideration alongside the rapid scientific progress.

The Natural Origin of CRISPR

The CRISPR-Cas system was not an invention created in a laboratory. It is a naturally occurring, sophisticated Immune System that prokaryotic cells (bacteria and archaea) use to defend themselves. They use it against external viral invaders called Bacteriophages.

Understanding this bacterial defense mechanism is crucial for scientists. It reveals the elegant efficiency and specificity that makes the system such a powerful tool.

A. The Bacterial Defense System

Bacteria face a constant, immense threat from phages. Phages inject their own DNA to successfully hijack the host cell’s machinery for replication. The CRISPR system is their elegant, molecular line of defense against these relentless attacks.

-

The first time a bacterium survives a phage attack, it captures and integrates a small piece of the viral DNA into its own genome. This small piece is inserted into the special CRISPR Locus.

-

These integrated viral sequences act as a molecular Memory Bank. They allow the cell to instantly recognize the same invader if it attacks again in the future.

-

The repeated, regularly interspaced viral segments give the CRISPR region its unique and descriptive name.

B. The Cas9 Nuclease

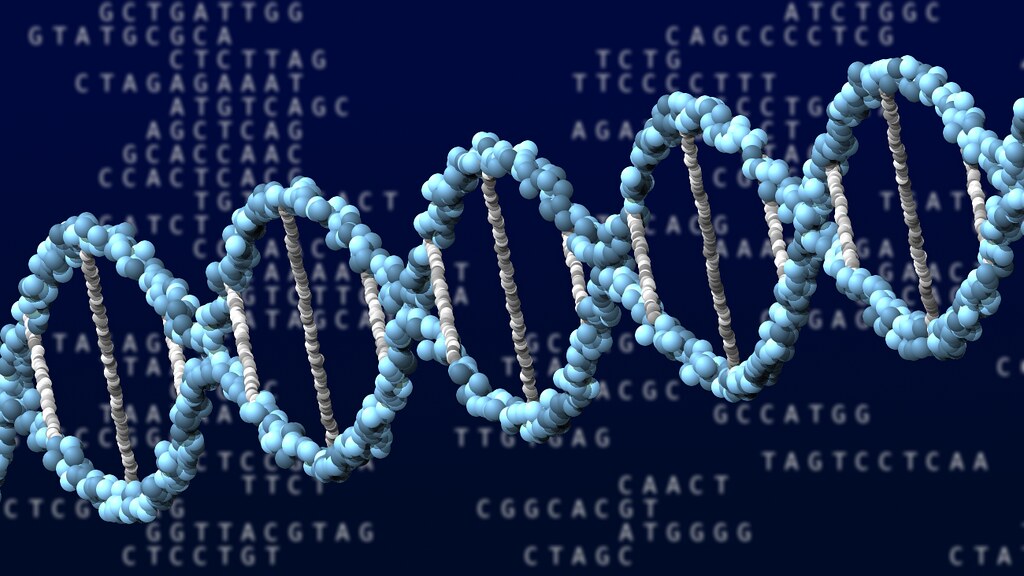

The key effector molecule in the entire system is the Cas9 Enzyme. This enzyme acts as the critical molecular scissor, performing the actual, physical cutting of the target DNA.

-

Cas9 is a highly specialized Nuclease. A nuclease is a type of enzyme that is specifically capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds that hold the DNA double helix together.

-

The enzyme does not cut randomly at all. It is strictly guided to the exact target location by a guide molecule. This provides the incredible precision the technology is known for.

-

Different bacteria utilize slightly different Cas proteins. However, Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes is the specific protein most commonly adapted for use in the laboratory.

C. The Guide RNA (gRNA)

The high specificity and immense power of the CRISPR system hinge on a single, short molecule called the Guide RNA (gRNA). This molecule is the “address label” that the Cas9 enzyme meticulously follows.

-

The gRNA is a single-strand RNA molecule. It is chemically engineered to contain a segment that is perfectly complementary to the DNA sequence the scientist wishes to target for editing.

-

The gRNA binds precisely to the Cas9 protein, forming a complex that navigates the cell’s nucleus. This complex then scans the entire genome, searching for the match.

-

When the complex successfully finds the DNA sequence that matches the gRNA, the gRNA binds to the DNA, precisely positioning the Cas9 enzyme to make its accurate cut.

The Mechanism of Gene Editing

Once the CRISPR-Cas9 complex has successfully identified and cut the target DNA, the cell’s own natural DNA Repair Mechanisms immediately spring into action. Scientists cleverly exploit these natural repair pathways to achieve their desired genetic modification.

This crucial process involves two main cellular repair pathways. Scientists control which specific pathway is activated to determine the final, engineered genetic outcome.

A. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is the cell’s simplest and fastest way to repair a double-strand break in its DNA. It is often described in the field as the “quick and dirty” repair mechanism.

-

NHEJ enzymes attempt to quickly ligate (glue) the two broken DNA ends back together instantly. This repair often occurs without using any template.

-

This quick repair frequently results in the addition or deletion of a few nucleotides right at the cut site. This small, spontaneous change is called an Indel.

-

The resulting indel often subtly shifts the entire reading frame of the gene. This typically renders the gene non-functional, a technique widely known as Gene Knockout.

B. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a much more precise but significantly slower repair mechanism. It strictly requires a template DNA sequence, which is typically provided by the scientist.

-

For HDR to occur, the scientist must introduce a custom-designed piece of Template DNA into the cell. This is delivered alongside the CRISPR-Cas9 components.

-

This template DNA contains the desired new sequence (the intended correction). It also has flanking regions that perfectly match the DNA near the precise cut site.

-

The cell then uses this template as a guide to repair the DNA break. This allows the precise insertion of new genetic material or the perfect correction of an existing mutation.

C. Base Editing and Prime Editing

While traditional CRISPR-Cas9 makes a double-strand break, newer, more refined technologies allow for changes without this potentially risky cutting action. These sophisticated methods offer increased precision and safety.

-

Base Editing involves strategically modifying the Cas protein to function as a chemical modifier rather than a cutter. This allows the conversion of a single DNA base (e.g., A to G) without breaking the backbone itself.

-

Prime Editing uses a specialized Cas enzyme chemically linked to an RNA transcriptase. It allows the system to directly “write” new genetic information into the target site with even greater flexibility and accuracy than before.

-

These sophisticated, non-cutting techniques significantly reduce the risk of Off-Target Effects. These are unintended cuts in other parts of the genome, thus increasing the technology’s safety profile.

Applications in Health and Medicine

The unprecedented ability to edit DNA with such high precision has instantly revolutionized the field of biomedical research globally. CRISPR holds the concrete potential to treat, and possibly permanently cure, thousands of currently incurable genetic diseases.

The applications span widely, from basic research conducted in a laboratory setting to clinical trials aimed at correcting serious human illnesses at their genetic root.

A. Somatic Gene Therapy

Somatic Gene Therapy involves editing the DNA in the cells of an individual patient’s body (somatic cells). Importantly, these specific changes affect only the treated individual and are never passed on to their children.

-

One primary clinical focus is treating debilitating disorders like Sickle Cell Disease and Beta-Thalassemia. Both are genetically caused by single-point mutations in blood cells.

-

Cells are carefully taken from the patient, precisely edited in the lab to correct the mutation, and then re-infused back into the patient’s body. This advanced procedure is called Ex Vivo Editing.

-

In some cases, the editing complex can be delivered directly into the patient’s body, targeting organs like the liver, eye, or muscle. This challenging procedure is called In Vivo Editing.

B. Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

Before treating human patients, CRISPR is an invaluable, essential tool for understanding the root causes of complex human diseases like cancer and Alzheimer’s.

-

Scientists use CRISPR to precisely introduce known disease-causing mutations into animal models (like mice) or human cell cultures. This creates accurate, realistic Disease Models.

-

These models allow researchers to observe the entire step-by-step progression of the disease. They can also test new therapeutic drugs against the exact cellular dysfunction.

-

The technology is also used to rapidly screen thousands of genes simultaneously. This helps identify which specific genes are necessary for cancer cell survival, revealing new potential drug targets.

C. Immunotherapy and Cancer Treatment

CRISPR is also rapidly accelerating progress in the crucial field of cancer immunotherapy. Specifically, it modifies a patient’s own immune cells to effectively seek out and destroy their tumor.

-

CAR T-Cell Therapy involves genetically modifying a patient’s T-cells (immune cells) to recognize and powerfully attack specific cancer antigens on the tumor surface.

-

CRISPR allows scientists to make multiple, precise edits to these T-cells simultaneously. This can significantly improve their potency, longevity, and ability to overcome the cancer’s complex defense mechanisms.

-

This capability to engineer a patient’s immune system provides a highly personalized and potentially curative approach to certain aggressive forms of cancer.

CRISPR in Agriculture and Ecology

Beyond human health and medicine, the affordability and simplicity of the CRISPR system have spurred a rapid revolution in agriculture and environmental science. It offers powerful, new tools for enhancing global food security and tackling ecological crises effectively.

The speed and precision of gene editing allow for the rapid introduction of desirable traits into crops and livestock. This bypasses decades of slow, traditional breeding techniques.

A. Crop Improvement

CRISPR is strategically used to improve essential agricultural traits without necessarily introducing foreign DNA from other species. This often makes the resulting products generally less controversial than older Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs).

-

Scientists can edit staple crops to dramatically enhance their Nutritional Value. This includes increasing essential vitamin content or removing common allergens like gluten.

-

The technology is used to quickly confer resistance to common agricultural Pests and Diseases. This significantly reduces the need for costly chemical pesticides and improves overall crop yield stability.

-

CRISPR allows for the rapid development of plants that are more resilient to extreme environmental stressors. Examples include resistance to drought, high salinity, and rising global temperatures.

B. Livestock Enhancement

Gene editing is also increasingly applied to livestock animals to improve overall animal welfare and the crucial efficiency of global food production.

-

Scientists have successfully used CRISPR to breed cattle that are naturally resistant to devastating viral diseases. This significantly reduces economic losses for farmers.

-

Editing is used to introduce traits that are intrinsically beneficial for animal health. This includes making dairy cows less susceptible to bacterial infections like mastitis.

-

In some experimental cases, the technology is used to genetically eliminate horns in cattle breeds. This ultimately improves safety for both the animals themselves and the farm workers.

C. Gene Drives and Ecology

Perhaps the most powerful and ethically controversial application outside of human medicine is the concept of a Gene Drive. This is a powerful, self-propagating genetic modification designed to spread.

-

A Gene Drive is an edited gene sequence designed to have a greater than $50\%$ chance of being inherited by offspring. It rapidly spreads a specific genetic trait throughout an entire population over successive generations.

-

Potential uses include controlling rapidly multiplying invasive species, reversing dangerous pesticide resistance in insect pests, and eliminating vector-borne diseases like malaria by making mosquitoes sterile or disease-resistant.

-

The ecological risks associated with a gene drive are immense. Once released into the wild, the modification is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to recall or stop, requiring rigorous regulation and careful ethical deliberation.

Ethical and Societal Considerations

The unprecedented power of CRISPR-Cas9 to alter the fundamental blueprint of life forces society to confront fundamental ethical, social, and policy questions immediately. The technology is advancing rapidly, often faster than the social consensus needed to guide its proper use.

These ethical considerations are absolutely essential. They must govern the application of gene editing, especially in humans, to prevent unintended consequences and deliberate misuse.

A. Germline Editing and Inheritance

The most intense and sustained ethical debate revolves critically around Germline Editing. This involves making genetic changes to human sperm, eggs, or early embryos.

-

Germline edits are inherently Heritable, meaning the changes are directly passed down to all future generations. This is fundamentally different from non-heritable somatic editing.

-

Proponents argue it could permanently eliminate devastating genetic diseases from family lines forever. Opponents raise serious concerns about unknown long-term health consequences and overall safety.

-

Most countries and leading international scientific bodies currently place a strict moratorium on human germline editing due to these profound ethical and safety concerns.

B. Safety and Off-Target Effects

Despite its advertised precision, the CRISPR system is not absolutely perfect or infallible. The possibility of unintended genetic changes remains a primary, major safety concern for any clinical applications.

-

Off-Target Effects occur when the Cas9 enzyme cuts DNA at a location in the genome that is only similar to the target sequence but not perfectly identical. This can potentially cause cancer or other genetic damage.

-

Scientists are continually refining the Cas enzymes and gRNAs to improve absolute specificity. However, the risk must be driven to near zero before any widespread human application.

-

Thorough screening and advanced sequencing technologies are necessary after every single edit to ensure the perfect integrity of the rest of the genome.

C. Equity and Access

The high cost and technological complexity of advanced gene editing raise serious questions about global equity and fairness. The technology should ideally benefit all of humanity, not just the wealthy few.

-

There is a major risk of creating a stratified society where only the affluent can afford to “cure” their children of genetic predispositions. This could significantly exacerbate existing health disparities worldwide.

-

The potential for Enhancement (editing genes for non-medical traits like intelligence or athletic ability) raises further societal concerns about social inequality and the commodification of human traits.

-

Policy frameworks are urgently needed to ensure broad, equitable access to legitimate gene therapies. This is essential while actively preventing the creation of a potentially dangerous genetic divide among people.

Conclusion

The advent of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system represents the most significant breakthrough in biology in decades, derived from a natural bacterial Immune System that uses the Cas9 Enzyme as a precise molecular scissor guided by a specialized Guide RNA. This powerful, versatile tool exploits the cell’s own repair mechanisms, utilizing Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) for gene knockout or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) for precise sequence correction.

The applications are already transforming Somatic Gene Therapy for diseases like sickle cell, accelerating Disease Modeling and enhancing Immunotherapy for cancer treatment. Beyond medicine, CRISPR is revolutionizing Crop Improvement and Livestock Enhancement for global food security, while the development of Gene Drivespresents both immense ecological potential and significant risk.

However, this profound scientific capability is inextricably linked to critical ethical debates, most notably concerning the heritable nature of Germline Editing and the need to minimize the safety risk of Off-Target Effects. Policy must therefore move swiftly to ensure Equity and Access, guiding the responsible deployment of this technology to benefit all of humanity while upholding fundamental ethical boundaries.