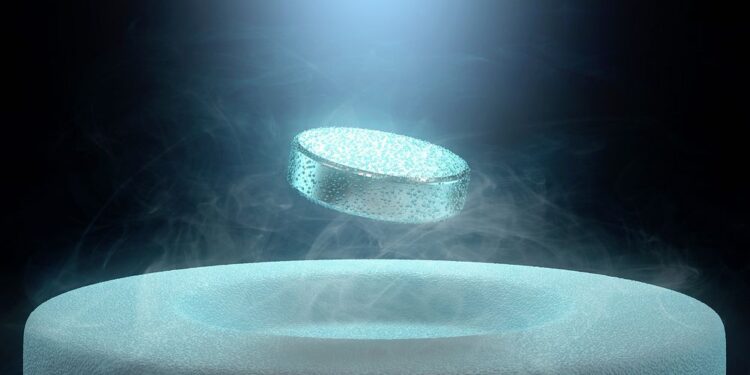

The Unique Foundation of Biological Systems

When we look around at the astonishing complexity and diversity of life on Earth, from the smallest bacterium to the largest redwood tree, it’s easy to overlook the simple, unassuming chemical element that makes it all possible: Carbon. This element sits strategically in the center of the periodic table. It possesses four valence electrons, which allow it to form four stable covalent bonds.

This unique bonding capacity grants carbon unparalleled versatility. It enables the element to link with itself and other elements in countless ways. This action constructs the massive, intricate molecules necessary for biological function.

Unlike silicon, the next most likely candidate, carbon can form strong, stable single, double, and even triple bonds. This capability results in long, branching chains, complex ring structures, and vast three-dimensional architectures. This versatility creates the enormous variation in molecular size and shape required to encode genetic information, catalyze metabolic reactions, and build cellular structures. Ultimately, the entire planet’s biosphere is a testament to carbon’s exceptional chemical geometry, making it the indispensable backbone of organic chemistry and the universal scaffold for life as we know it.

Carbon’s Chemical Versatility

Carbon’s ability to act as the central atomic scaffold for all organic molecules stems directly from its position in the periodic table. This specific atomic arrangement dictates its precise bonding behavior with other atoms.

Understanding this bonding versatility is the first crucial step toward appreciating how simple atoms can efficiently assemble into the complex, dynamic machinery of living cells.

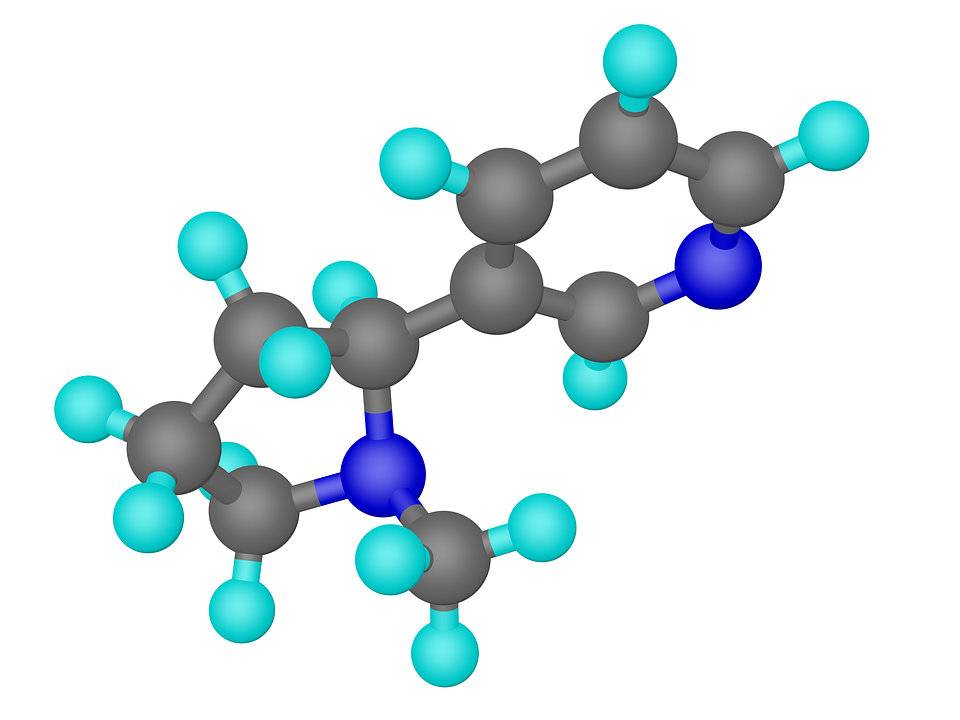

A. Quadrivalency and Covalent Bonds

The most important fundamental feature of the carbon atom is its Quadrivalency. This technical term means it consistently possesses four electrons available for bonding in its outermost shell.

-

Carbon must form exactly four chemical bonds to achieve a stable, full octet configuration, a state of low energy. It nearly always achieves this required stability by forming strong Covalent Bonds through the mutual sharing of electrons.

-

These specific bonds are strong enough to reliably withstand the dynamic chemical environment within a living cell. They are also flexible enough to allow for conformational changes that are essential for biological activity.

-

This consistent four-bond structure naturally dictates a fundamental tetrahedral geometry. This allows for intricate, three-dimensional structures rather than simple flat, two-dimensional shapes.

B. Carbon Skeletons and Chains

Carbon’s unparalleled ability to bond robustly and strongly with other carbon atoms is chemically called Catenation. This is the key distinguishing property that allows for the creation of massive, complex biological molecules.

-

Carbon atoms can link together almost indefinitely to form stable Carbon Skeletons. These skeletons can exist as straight chains, extensive branched networks, or robust closed ring structures.

-

The immense variety in length, branching patterns, and double bond positions allows for an astronomical number of possible molecular structures. Each distinct structure can efficiently serve a unique biological purpose.

-

These long, stable chains fundamentally form the backbone of all the major macromolecules. This includes the long fatty acid chains in lipids and the complex sugar rings found in carbohydrates.

C. Multiple Bond Formation

Unlike most other common elements, carbon easily and stably forms single, double, and even triple bonds. It forms these multiple bonds both with itself and with other crucial elements like oxygen and nitrogen.

-

A Double Bond involves the sharing of four total electrons between two carbon atoms, which creates a stronger link. A Triple Bond involves the sharing of six electrons, creating the strongest link.

-

These multiple bonds rigidly restrict the rotation around the bond axis. This restriction introduces necessary rigidity and geometric variations (like cis and trans isomers) that are critical for molecular function.

-

This ability to manage both bond type and geometry allows carbon to create both the flexible structure of lipids and the rigid, information-storing structure of DNA bases.

Functional Groups and Chemical Reactivity

While the long carbon skeleton provides the basic architectural structure, the highly specific chemical properties and reactivity of a molecule are determined by the attachment of specific Functional Groups.

These critical groups are small, specific clusters of atoms. They are repeatedly found in different organic molecules and instantly confer distinct chemical characteristics upon the molecule they are attached to.

A. Hydroxyl and Carbonyl Groups

Two of the most common and fundamentally essential functional groups involve the element oxygen. These groups efficiently introduce polarity and create specific sites for chemical reaction.

-

The Hydroxyl Group (-OH) is characteristic of alcohols and simple sugars. Its polarity makes the molecules hydrophilic, enabling them to dissolve readily in the aqueous environment of water.

-

The Carbonyl Group (C=O) is prominently found in sugars and is central to energy storage and cellular metabolism. It significantly increases the attached molecule’s chemical reactivity.

-

The specific location of the carbonyl group (either internal or terminal) differentiates ketones from aldehydes. This leads to subtle but important chemical differences in various sugar molecules.

B. Amino and Carboxyl Groups

These two distinct groups are absolutely central to the chemistry of proteins. They precisely define the building blocks of life: the amino acids.

-

The Amino Group ($\text{-NH}_2$) chemically acts as a base. It attracts protons ($\text{H}^+$) from the surrounding solution, a critical function essential for buffering pH changes in the cellular environment.

-

The Carboxyl Group ($\text{-COOH}$) chemically acts as an acid. It can readily donate a proton, which is critical for defining the acidic nature of amino acids and fatty acids.

-

The simultaneous presence of both the amino group and the carboxyl group in amino acids allows them to polymerize readily into long polypeptide chains.

C. Phosphate and Sulfhydryl Groups

Other vital functional groups introduce high potential energy and important cross-linking capabilities to crucial biological molecules.

-

The Phosphate Group ($-\text{OPO}_3^{2-}$) consistently carries a negative charge and is found in the backbone of DNA and in the high-energy molecule ATP. Its presence is vital for all forms of energy transfer.

-

The Sulfhydryl Group (-SH) is uniquely found in the amino acid cysteine. It forms stable, strong disulfide bridges (-S-S-) which are crucial for maintaining the precise three-dimensional structure of many proteins.

The Four Major Macromolecules

Life’s incredible, organized complexity arises from the precise polymerization of simple carbon-based monomers into four fundamental classes of Macromolecules. These massive molecules collectively perform all the structural and functional tasks necessary for life.

These four molecular families are the core, indispensable pillars of cellular biology. Each family plays a specialized, essential role in the maintenance and function of the living cell.

A. Carbohydrates: Energy and Structure

Carbohydrates are constructed from simple sugar monomers, the most common and vital being glucose. They serve as the cell’s primary short-term energy source and provide critical structural support.

-

Monosaccharides, like glucose and fructose, are directly used by the cell for immediate energy production through the process of cellular respiration.

-

Polysaccharides, like starch and glycogen, are utilized as long-term energy storage forms. Starch is used in plants and glycogen is used in animals.

-

Cellulose, another structural polysaccharide, forms the tough, rigid structural component of plant cell walls, giving plants their necessary strength.

B. Lipids: Membranes and Storage

Lipids (fats, phospholipids, and steroids) are a highly diverse group of non-polar, hydrophobic molecules. They are not true polymers but are essential for energy storage and cell boundary formation.

-

Triglycerides (fats) are incredibly efficient, long-term energy storage molecules. They consistently contain more than twice the energy per gram compared to carbohydrates.

-

Phospholipids are the critical, necessary building blocks of all cell membranes. Their unique structure creates the stable bilayer that forms the fundamental cell boundary.

-

Steroids, such as cholesterol and various hormones, serve vital roles in cell signaling and are crucial for maintaining membrane fluidity and stability.

C. Proteins: Workhorse Molecules

Proteins are arguably the most versatile and functionally diverse molecules of life. They are complex polymers built from long, precise chains of amino acid monomers.

-

Proteins perform almost every task in the cell, acting as highly specific Enzymes to catalyze reactions, providing Structural Support, and facilitating intricate Cell Signaling pathways.

-

The complex function of a protein is determined entirely by its complex, folded three-dimensional shape. This final shape is dictated by the precise sequence of the 20 different amino acids in its chain.

-

Examples include keratin (which provides structure in hair and nails), hemoglobin (responsible for oxygen transport in blood), and antibodies (critical for defense against pathogens).

D. Nucleic Acids: Information Storage

Nucleic Acids (DNA and RNA) are polymers specifically constructed from nucleotide monomers. They are the unique, indispensable carriers of the cell’s genetic, inheritable information.

-

DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) stores the complete, stable genetic code in the cell’s nucleus. It serves as the master blueprint for all protein synthesis.

-

RNA (Ribonucleic Acid) acts as the necessary working copy. It is crucial for transferring the genetic information from the DNA to the protein-building machinery outside the nucleus.

-

The repeating sugar-phosphate backbone and the precise sequence of the four nitrogenous bases (A, T, C, G) constitute the exact language of heredity.

The Mechanism of Polymerization

The creation of these massive biological polymers from simple monomers is a highly controlled, repetitive chemical process that occurs constantly within the living cell.

This fundamental, enzyme-driven mechanism ensures the precise, non-random assembly of the giant carbon-based molecules that form the very essence of life.

A. Dehydration Synthesis (Condensation)

The fundamental chemical reaction used to consistently link monomers together and build polymers is called Dehydration Synthesis. This energy-requiring process requires the removal of a water molecule.

-

During this crucial reaction, a hydroxyl group (-OH) is removed from one monomer. Simultaneously, a hydrogen atom (-H) is removed from the other joining monomer.

-

These removed atoms immediately combine to form a molecule of water ($\text{H}_2\text{O}$). This allows the two monomers to bond together covalently at the vacant sites.

-

This synthesis process strictly requires an input of energy and must be catalyzed by specific enzymes. It is the core process that builds proteins, nucleic acids, and complex carbohydrates.

B. Hydrolysis: Breaking Down Polymers

The exact reverse reaction, which is used to efficiently break down the large polymers back into their constituent monomers, is called Hydrolysis. This process requires the direct addition of a water molecule.

-

A molecule of water ($\text{H}_2\text{O}$) is added across the covalent bond linking the two monomers. The water molecule is chemically split into $\text{H}$ and $\text{OH}$.

-

The hydroxyl group (-OH) is attached to one monomer, and the hydrogen atom (-H) is attached to the other. This action effectively breaks the chemical bond between them.

-

This breakdown reaction naturally releases energy and is the primary mechanism utilized during digestion to break down large food molecules into forms the body can successfully absorb.

C. Directionality and Sequence

Biological polymers are inherently directional, meaning they possess distinct, chemically different ends. This crucial Directionality is absolutely essential for information storage and proper molecular function.

-

Nucleic acids have a 5′ end (defined by the phosphate group) and a 3′ end (defined by the hydroxyl group). This defines the consistent reading direction of the genetic code.

-

Proteins have an N-terminus (defined by the amino group) and a C-terminus (defined by the carboxyl group). This defines the beginning and end of the polypeptide chain.

-

The precise, non-random sequence of monomers in a polymer is the master determinant of its biological function. For example, the amino acid sequence dictates the protein’s final shape.

Chirality and Molecular Recognition

The three-dimensional, tetrahedral geometry of carbon’s bonds introduces a crucial, subtle property known as Chirality(or handedness). This spatial property is absolutely vital for life’s high degree of specificity.

The cell’s ability to precisely distinguish between mirror images of the same molecule is central to the precise, non-chaotic mechanics of all biochemical processes.

A. Chiral Centers and Enantiomers

A Chiral Center occurs specifically when a carbon atom is covalently bonded to four different atoms or functional groups. This creates two distinct, non-superimposable mirror-image forms.

-

These specific mirror-image molecules are called Enantiomers (or optical isomers). They are identical in chemical formula but differ only in their three-dimensional spatial arrangement.

-

Think of your left and right hands as an analogy: they are perfect mirror images, but you cannot perfectly superimpose one onto the other by rotation alone.

-

The presence of these chiral centers vastly increases the structural diversity possible for complex carbon-based molecules, allowing for greater complexity.

B. Life’s Homochirality

Despite the fact that non-biological organic synthesis typically creates equal amounts of both mirror-image forms (a racemic mixture), life on Earth exhibits universal Homochirality. This means it strictly uses only one form.

-

All amino acids used to efficiently build proteins in living organisms are exclusively the L-isomer (left-handed form), with the exception of the simple amino acid glycine.

-

Conversely, all sugars used in biological systems (like the sugars in DNA and glucose) are exclusively the D-isomer(right-handed form).

-

This extreme molecular selectivity ensures that enzymes, which are highly specific, only interact with the correct molecular shape, preventing harmful, chaotic side reactions.

C. Molecular Recognition

The highly specific, lock-and-key interaction between crucial biological molecules is based entirely on the precise three-dimensional shape, including chirality. This recognition process is called Molecular Recognition.

-

An enzyme’s active site will only physically accommodate the correct enantiomer of its substrate. The mirror-image form is often completely inert, inactive, or sometimes even toxic to the cell.

-

The differing pharmacological effects of certain drugs, where one enantiomer is therapeutic and the other is harmful, strongly underscore the critical importance of chirality in biochemistry.

Conclusion

The exceptional chemical behavior of Carbon, rooted in its ability to form four stable bonds and undergo extensive Catenation, is the singular reason why this element serves as the universal Backbone of Life on Earth. This unique versatility allows simple atomic components to assemble into the astonishing variety of complex Macromolecules—including energy-storing Carbohydrates, membrane-forming Lipids, versatile enzymatic Proteins, and information-rich Nucleic Acids.

The precise function of these giant molecules is dictated not only by the sequence of their monomers but also by the specific Functional Groups attached to the carbon skeleton, which impart critical chemical properties like acidity or polarity. The fundamental processes of building these structures, through Dehydration Synthesis, and breaking them down, via Hydrolysis, govern all metabolism and growth within the cell.

Furthermore, the subtle yet crucial concept of Chirality ensures that biological systems maintain strict Homochirality, allowing the highly specific, lock-and-key interactions essential for efficient, non-chaotic biochemistry. In essence, life’s complexity, information capacity, and dynamic function are all direct consequences of carbon’s unmatched ability to form stable, diverse, and geometrically specific molecular scaffolds, making it the truly indispensable element of the biosphere.